Beggar, during happier days. credit Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, NMFS permit no. 15543

A group of boaters feed Beggar the dolphin illegally near the Albee Road Bridge.

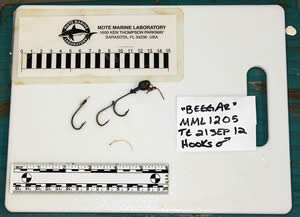

Hooks and line removed from Beggar's stomach during a necropsy at Mote Marine Lab. credit Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, NMFS permit no. 15543

One of Sarasota's most well known and ill-fed dolphins was found dead near the Albee Road Bridge in Sarasota on Friday, 9-21-12. Known as "Beggar," the bottlenose dolphin was one of the most studied wild dolphins in the world and an example of how human behavior can sometimes hurt wild animals.

Beggar frequented the Albee Road Bridge area of the Intracoastal Waterway, often approaching and being approached by boaters who fed and attempted to pet him. He was the subject of numerous scientific papers and public education campaigns designed to help humans learn that feeding and petting wild dolphins is bad for the animals. It is also illegal under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Violations can be prosecuted in civil or criminal court and are punishable by up to $100,000 in fines and up to one year in jail per violation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently prosecuted three such cases in Florida.

By feeding Beggar, people changed his behavior and put him at an increased risk from boat strikes. It also appeared that other dolphins learned similar "begging" behavior by watching him interact with humans.

The dolphin was found floating in the water late Friday afternoon near Mile Marker 15 of the Intracoastal Waterway, just north of the Albee Road Bridge. The body was recovered by Sarasota County Marine Patrol, which towed the dolphin to a boat ramp so Mote's Stranding Investigations Program could pick it up. A member of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, which has studied the dolphins of Sarasota Bay for 42 years, identified the animal as Beggar.

Gretchen Lovewell, manager of Mote's Stranding Investigations Program, performed a necropsy, or animal autopsy, on Beggar Friday evening. The animal's body was in a state of moderate decomposition and no definitive cause of death could be pinpointed. However, there were numerous findings indicating that his interactions with humans played an overall role in Beggar's ill health.

- Externally, there were healed boat wounds on the dorsal fin, a healed puncture wound on the right pectoral fin, a possible boat wound on the right side of the body, below the dorsal fin and a healing puncture wound between the blowhole and the dorsal fin.

- Beggar had multiple broken ribs and vertebrae.

- While he did not have much food in his stomachs, there were three fishing hooks and small bits of line in the first stomach, two squid beaks (not a normal prey item for resident Sarasota Bay dolphins) and several ulcers of varying severity in the third stomach.

- He was dehydrated â€" possibly because he was not eating a normal dolphin diet.

In addition to these wounds, Lovewell also found internal injuries from two stingray barbs. One barb had migrated through the ribs and embedded near the small intestine with necrotic tissue surrounding the barb. The second barb was found near the right shoulder blade and was very close to puncturing the thoracic cavity (near the lungs).

"We can't say which of these many injuries was the ultimate cause of death for Beggar," Lovewell said. "But all of our findings indicate that he was in poor health for a long time and that his interactions with humans played a role. Boat strike wounds, fishing hooks and line in his stomach â€" even the squid beaks we found â€" all of these things indicate that he was spending more time attempting to get food from humans than foraging on his own."

Beggar had been frequenting the area where he was found dead for more than 20 years. From March to June 2011, Dr. Katie McHugh of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, a partnership between Mote and the Chicago Zoological Society, spent 100 hours observing his behavior and that of the boaters who encountered him. She documented:

- 3,600 interactions between Beggar and humans â€" up to 70 per hour;

- 169 attempts to feed him 520 different food items â€" everything from shrimp and squid to beer, hot dogs and fruit;

- 121 attempts to touch him â€" resulting in nine bites to the humans doing the petting.

"Compared to the other wild dolphins we study in Sarasota Bay, Beggar was not a healthy dolphin," McHugh said. "In addition to his unnatural feeding behavior, Beggar also had very limited social interactions with other dolphins and moved over an extremely small range when compared to most adult male dolphins."

During McHugh's study, she also looked at what humans and Beggar did when NOAA law enforcement officers were present. When officers were on the water, boaters were much less likely to approach Beggar and Beggar was much more likely to forage for food when humans stopped giving him handouts.

Beggar's death offers a stark reminder of why feeding wild dolphins is bad, said Dr. Randy Wells, director of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program. "By feeding Beggar, people reinforced the bad behavior that eventually played a role in his death. Ultimately, it's human behavior that we need to change. We need to make sure that this pattern doesn't repeat itself with another dolphin."

Stacey Horstman, NOAA Fisheries Bottlenose Dolphin Conservation Coordinator, appealed to the public for help on the issue. "Beggar was a local icon and tourist attraction for over two decades, and the results of this necropsy are a reminder of how people's actions are harmful to wild dolphins," she said. "There is a common misconception that feeding, touching, and swiming with dolphins is not harmful and that they don't get hit by boats. We are concered about how frequently the public and anglers continue to feed wild dolphins, as Beggar is just one of many wild dolphins in the southeast U.S. that have been fed by people and learned to associate people with food. Responsibly viewing wild dolphins is crucial to their survival and we are asking the public for help so dolphin populations stay healthy and wild for generations to come."