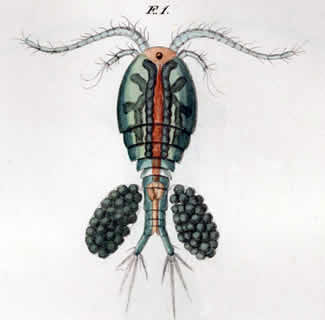

Copepods like the one have much to tell scientists. (Credit: Wisconsin A. Vernalis)

A new study has revealed that what was once believed to be a single copepod species is really a collection of many species.

A common and widespread species of freshwater plankton, called a copepod, forms new species at an uncommonly high rate, scientists have discovered. Indeed, a new study has revealed that what was once believed to be a single copepod species is really a collection of many species.

Grace Wyngaard, a biologist at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., and colleagues Andrey Grishanin of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Ellen Rasch of East Tennessee State University and Stanley Dodson of the University of Wisconsin-Madison published their study in the current issue of the journal Evolution.

"The process of forming new species has been cited as one of the most important research topics in biology," said Sam Scheiner, program director in the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research. "This study provides critical evidence that the ways species form and evolve are more complicated than we had previously understood."

Copepods, microscopic crustaceans that inhabit lakes, ponds, rivers and ditches, serve as the main diet for many fish.

"Some identically appearing forms collected from the same pond cannot mate and produce young, thus defining them as different species," said Wyngaard. "By following the parents and offspring of these plankton in the laboratory, we discovered that they reorganize their DNA dramatically from one generation to the next."

The team collected the copepods from several Wisc. ponds. Because enough variation occurred to significantly alter the animals' genetics in just a few laboratory generations, "The number of copepod species may be much higher than current surveys of freshwater environments lead us to believe," Wyngaard concluded.

She and her colleagues suggest DNA in the genomes of some zooplankton may be organized in a way that allows new, and sometimes successful, combinations of genes to arise quickly.