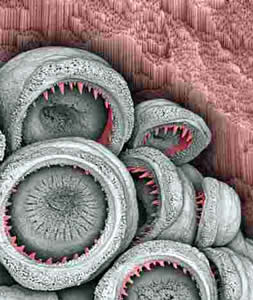

Squid suckers and their constituent rings (highlighted in red) are very effective at immobilizing captured prey.

An individual sucker ring from the Humbolt squid. The triangular dentitions, ready to pierce the skin of prey, are clearly seen at the top of the ring

A chance encounter with a Humboldt squid on a fishing trip left quite an impression on James Weaver, a research associate at UCR's Bourns College of Engineering. In fact, the lasting impression also provided the impetus for further research conducted by an interdisciplinary team from several institutions and headed by Professor Henrik Birkedal of the Department of Chemistry and the Interdisciplinary Nanoscience Center, Aarhus University, Denmark, and Professor David Kisailus of the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering in the Bourns College of Engineering.

The idea for studying the architectural and mechanical properties of these structures originated on a trip to collect research specimens in Ventura, Calif., aboard a sport fishing boat

"While removing a hook from one of the meter-long squids, its tentacles wrapped tightly around my arm and inflicted significant damage as I tried to free myself," said Weaver. "The sheer damage that these structures were capable of inflicting intrigued me greatly."

The large, aggressive predatory Humboldt squid, Dosidicus gigas, grips onto prey with a set of suckers that line its tentacles. Each of these suckers contains a rigid disc lined with formidable triangular teeth that significantly increase their gripping power during prey capture and handling. Researchers are now surprised to find that these sucker rings are nanostructured and made entirely of protein. This research is reported as the cover story in the Jan. 26, 2009 issue of Advanced Materials.

In addition to Birkedal, Kisailus and Weaver, the paper was authored by Ali Miserez (University of California, Santa Barbara), Peter B. Pedersen (Aarhus University, Denmark), Todd Schneeberk (University of California, Santa Barbara), and Roger T. Hanlon (Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Mass.). The research team spans the fields of chemistry, marine biology, molecular biology and materials science. Only with this interdisciplinary team was the group able to glean the secrets of the grip of this impressive beast.

"The exciting part of this research from an engineering perspective is that we can now begin to design a myriad of multifunctional materials with applications for automotive, aerospace, sports, and medical industries," Kisailus said.

Because of the unique properties of these structures, a special set of analytical tools was required for investigating their composition.

"The techniques used in this study are rather different than those used for investigating other hard tissues or even engineering materials because we are dealing with a wholly organic biological structure, said Ali Miserez from the Materials Department and the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, UC Santa Barbara and the article's lead author.

The first surprise that gripped the research team was that the sucker rings contained a network of nano-porous channels that were oriented parallel to the long axis of the teeth. These channels are between 100 – 250nm in diameter, increasing from the outer surface to the inner core of each tooth.

"This unique organization results in a material that is abrasion-resistant on the exterior, while maintaining a flexible core," Birkedal said. "This is accomplished solely by altering the local pore fraction, without significantly changing the composition of the material from which the sucker rings are constructed."

The sucker rings have long been assumed to be made of the sugar-based polymer chitin that comprises the beak of the Humboldt squid and is a common structural material in invertebrates such as arthropods and other mollusks. It was therefore surprising that the researchers could not find any trace of chitin, but instead discovered that the sucker rings are likely held together primarily by hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds.

UCR's Kisailus and Weaver are also currently working with General Motors Research & Development headquartered in Warren, Mich., on research involving the inner pearly layer (nacre) of the abalone shell with the goal of replicating its unique properties in man-made materials.

"A primary focus of our Biomimetic and Nanostructured Materials Lab is to understand fundamental structure-function relationships in biological structures so that we can develop light-weight and tough synthetic materials that could be used for aerospace, automotive and medical applications," Kisailus said. "The resulting multifunctional materials could be produced at significantly lower processing costs and under environmentally benign conditions while maintaining their unique architectures and mechanical properties."

Birkedal's laboratory in Aarhus Denmark focuses on biological materials and bio-inspired materials chemistry.

"Nature excels at integrating nanomaterials into functional three-dimensional hierarchical structures, like miniature Eiffel Towers. This type of integration can lead to completely new materials," said Birkedal. "Therefore we study materials from biology in our laboratory to derive inspiration for new types of synthetic functional materials. Understanding structure at several length scales, from the molecule to the centimeter, is a major challenge and one of the key objectives in our research."

Kisailus added, "Based upon our latest findings from Dosidicus that demonstrated tough materials can be synthesized from purely organic, non-crystalline materials, we have now opened the door to new and exciting opportunities in engineering materials design and synthesis."